Imbolc and the Two Brigids

In a world where we can turn up the thermostat when we get cold, it’s hard to imagine the sufferings of our agrarian Celtic ancestors in winter, centuries ago.

Light and heat were generated by fire. Shelter and warm clothing for all but the rich was woefully inadequate. Starvation was a constant threat. If harvests had been poor; if precious livestock perished in the bitter cold, or from lack of adequate feed, new calves and lambs would not be born. The necessary food supply would fail, and scores of people, particularly the young, the old and the vulnerable, would perish.

Imagine then the joy of common folk when Imbolc arrived! In the Pagan world, Imbolc is the 2nd of the four Sabbats dividing the Celtic year into winter, spring, summer and fall. Its arrival on February 1st is greeted with relief and celebration! Half of winter had passed away. The bitter Crone months were over, and the arrival of Brigid, the Spring Maiden, heralded the great turning of the year back toward the sun, and renewal of the Earth.

With Brigid’s return, days gradually lengthened, winter’s grip loosened, and seeds quickened. The birth of lambs or calves was a sure sign of spring. The Druid’s name for Imbolc was “oimelc,” meaning ewe’s milk. Milk to our ancestors was sacred ~ as sacred, some say, as communion wine to the Christian. It symbolized a reverence for the Great Mother who was seen as the source of all life.

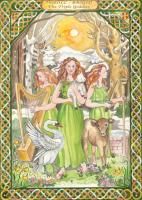

Brigid is a Celtic triple goddess of fire. At her birth, it is said, a column of fire rose from the top of her head to the heavens. As Sun Goddess, she is the Light Bringer who presides over hearth and forge. She inspires the divine creative light of poets, musicians, artists and craftswomen. She nurtures crops, livestock and nature, generates fertility, and assists at childbirth. As Great Mother, she leans over every cradle. She is a mistress of divination whose sacred wells bring healing and glimpses into the future.

Her ancient names run the gamut of human experience. As war goddess, she was called the Flame of Ireland and Fiery Arrow. Other names were Brigid of the Harp, Mother of Songs and Music, Brigid the Sorrowful (she lost a beloved son and brother), Bride of Joy, Brigid of the Green Mantles, and Brigid of the Slim Fairy Folk. As Bride of the Flocks, swans accompanied her, and believers looked for the print of a swan’s foot in the ashes of their smoored fires as evidence of her passage. Her special animals, the domestic cow and the sheep, reflected her concern for the feeding of families with meat and milk.

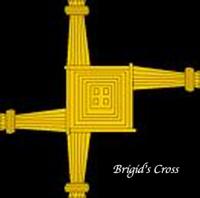

In towns and rural communities, the Day of Bride was a celebration of women, a feminine festival. Young girls dressed in white went through their villages, handing out Brigid’s Cross to every household. An effigy of Brigid, created of straw, dressed and adorned with ornaments, might be carried through the town. Maidens might gather in a single house, where young men would visit and pay respectful court to them. Special foods were prepared, shared, and set outside or on the hearth to feed the goddess. Strips of ribbon or clothing were left on doorsteps, to receive her blessing, then hung, as protective talismans, in barns and homes.

Around 453 AD, the powerful energy of the great goddess was transformed by the Catholic Church into St. Brigid, and given a new biography. Following their policy of absorbing Pagan festivals into Christian feast-days, the Day of Bride was converted into Candlemas, the feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin, celebrated on February 2nd. In this way, Brigid made the great leap from pagan Mother Goddess, to worship of the Virgin Mother by a Virgin Saint.

There were holdovers from her worship. Candlemas was celebrated with candlelight processions, hearkening back to the goddess’s role as Light Bringer. St. Brigid’s story reflected her Pagan roots in many respects. Her legend states that she was the illegitimate daughter of an Irish Chieftain and a Christian slave. Born at sunrise, it is said that the cottage where she lay glowed with fire. Her mother bathed her in milk, before handing her over to a Druid who was charged with raising her. Her father, a follower of the Old Religion, named her Brigid, after the great Celtic goddess.

We don’t know how she came to convert to Christianity, but it may have been through the influence of her Christian mother ~ or perhaps through a chance meeting with the charismatic Christian missionary, St. Patrick. Following her conversion, she and all her companions, former worshippers of Brigid, became followers of Christ and of His mother, Mary. They started Ireland’s first religious community of women. Based on her reputation for saintliness and love for the people, legends grew claiming that she was the midwife to Mary, the Mother of Jesus, and Foster Mother to the Savior. Her popularity in Ireland is second only to St. Patrick himself.

St. Brigid founded the first Irish convent in Kildare, in a monastery sited at a shrine to Brigid. Virgins who had guarded an eternal flame for the goddess gave way to her namesake and her community of nuns, who re-dedicated the flame to Christ. St. Brigid’s monastery became a great center for learning, the arts, and spirituality. The school of art that St. Brigid founded at Kildare produced illuminated manuscripts that became famous throughout Christendom.

This remarkable woman tended the eternal flame until her death on February 1 (Imbolc!) in 525 AD. On Imbolc of 1993, the Daughters of the Flame relit a fire in honor of the goddess.

One of the symbols associated with St. Brigid is the Cross of Brigid, a four-legged cross woven from rushes. She is said to have made this cross while explaining Christ’s story to a dying pagan. Even today, people make these crosses and place them in barns and houses on St. Brigid’s day, as protection from evil. Find out how to make your own Brigid’s Cross on Google!

It is fascinating to consider that the qualities and gifts of the great Celtic goddess, Brigid, are not lost, but rather reincarnated and reinterpreted in the life of Ireland’s greatest female Christian saint. For me, this indisputable fact demonstrates the immense power of folk religion to survive all efforts to suppress it ~ and to continue to inspire many who love the Earth, and hold the old ways and wisdom dear. There is no conflict in this. All is absorbed into the wonder of this vast universe in which “we live, and breathe, and have our being.”

A Gaelic poem about Brigid asserts that she “…put songs and music on the wind before ever the bells of chapels were rung in the West or heard in the East.” How true. And yet, after those bells were rung, St. Brigid’s monastery continued in Brigid’s footsteps, and became a bastion of culture and the arts in a wild, untamed country.

The songs of both Brigids still sing in the hearts of those who honor their power to inspire and transform. Their flame will never go out.